When dead bees are a welcome sight!

Dead bees a welcome sight?

Yeah, you heard me right. Now let me explain…

Usually seeing dead bees is a terrible thing to behold for a beekeeper. A good deal of sadness whelms up when opening up a box and finding the colony dead or having absconded. It’s like losing a friend…or 30,000 of them. But yesterday it brought me a glimmer of hope and resulted in a very positive confirmation. Why in the world would that be?

Usually seeing dead bees is a terrible thing to behold for a beekeeper. A good deal of sadness whelms up when opening up a box and finding the colony dead or having absconded. It’s like losing a friend…or 30,000 of them. But yesterday it brought me a glimmer of hope and resulted in a very positive confirmation. Why in the world would that be?

It’s winter up here in Flagstaff. And that means snow. And more snow. And then it snows again. Welcome to life in the mountains, my friends. This potentially creates a problem for both bees and beekeepers alike. When winter sets in there’s a very real chance that some hives may not make it through the long cold. Bees have been given a great deal of intelligence and can often survive in most cold environments for a period of time. But extreme cold or extreme length of winter can spell doom for our little friends.

Bees do have a coping mechanism, however. Much like antarctic penguins, the bees will ball up in cold times, and will rotate from outside to inside in a slow spiral dance, while vibrating their bodies to produce heat and keep the bee-ball warm. Of course, right in the middle of this dance is the main lady of the royal ball…the queen. They rotate around her, ensuring she is kept warm, while other bees take turns pulling food stores from the comb to bring back to feed her and other bees. They can keep this up as long as they have the energy received from food supplies in the hive, or as long as it doesn’t get too cold to keep things warm. That was my fear recently.

You see, we recently had some VERY cold temperatures. When I was out in Parks last week I recorded -24F degrees. That was the coldest I’ve ever seen in my life! And that is a potential danger for losing a hive. Even for local native bees here in Flagstaff. But what a difference a week can make! Just one week later we went from near-record cold to near-record high temps for this time of year. Nearly 60 degrees and sunny yesterday all around the region!

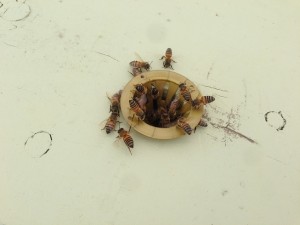

After spending the day at the Grand Canyon I decided to check in on our Parks pollination colony on the way back to see how things were. Since it was so warm I knew a quick curious peek wouldn’t harm them and chill the hive. As I tromped through the snow and approached the hive I noticed it…DEAD BEES ON THE SNOW! Now, most would be saddened by this, but I was glad. Why? Because dead bees can’t fly themselves out of a hive and onto the ground. What the dead bees outside the hive meant was that the colony was probably pretty strong and had been “cleaning house”. Yes, throughout the winter bees will die in the hive, and they will drop to the bottom of the box awaiting the undertaker. When the weather warms up other worker bees go about cleaning up the place. They will carry dead bees out of the hive and drop them on the ground. They will also use the time to fly out of the hive and use the bathroom outside. They’re pretty clean that way.

After spending the day at the Grand Canyon I decided to check in on our Parks pollination colony on the way back to see how things were. Since it was so warm I knew a quick curious peek wouldn’t harm them and chill the hive. As I tromped through the snow and approached the hive I noticed it…DEAD BEES ON THE SNOW! Now, most would be saddened by this, but I was glad. Why? Because dead bees can’t fly themselves out of a hive and onto the ground. What the dead bees outside the hive meant was that the colony was probably pretty strong and had been “cleaning house”. Yes, throughout the winter bees will die in the hive, and they will drop to the bottom of the box awaiting the undertaker. When the weather warms up other worker bees go about cleaning up the place. They will carry dead bees out of the hive and drop them on the ground. They will also use the time to fly out of the hive and use the bathroom outside. They’re pretty clean that way.

As I walked up to the hive I saw a lone bee flying back and forth to the entrance and back out again and I knew there was hope. So I popped open the top lid, and what did I see? Bees packing the entire box and all the way up to the top frames of a double deep stack of boxes. Not a few bees. Not sick, lethargic bees. But LOTS of bees, moving all around the frames just how I left them in the Fall! I must say I was surprised, to say the least. Having not checked in on them since October and having multiple nights of subzero temperatures I was sure they had frozen to death or had eaten all their honey stores in futility while trying to generate heat to stay warm. But there they were, a golden moving carpet on every frame, as healthy as a bee can be.

So, to you who are new beekeepers. Don’t fear should you see a few dead bees outside the hive during winter, especially after the reprieve of a warm sunny day. Should you see a pile of dead bees, rest assured that the undertaker is well at work, the workers peppering the ground have now crossed the river Styx, and your bees are probably alive and buzzing about on the inside just awaiting the new spring blooms and sweet nectar once again!